Last Friday, my new favorite NPR podcast, Pop Culture Happy Hour, tipped me off that Parasite was a fabulous film and true contender for Best Picture. Seeing it only the night before the Oscars aired, my awe at its creative brilliance was still fresh allowing me to celebrate as it won award after award.

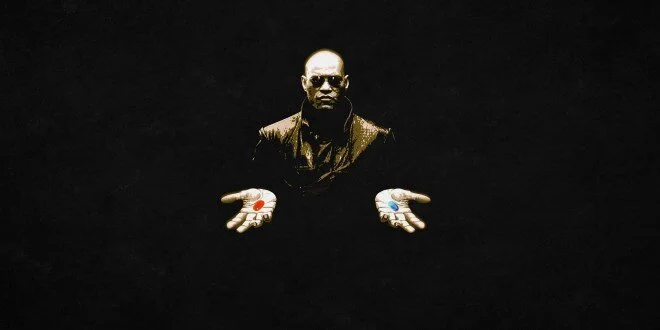

There are so many praiseworthy aspect of Bong Joon-Ho’s stunning film but I most valuabled its expansion of my view of privilege. Much like Roald Dahl uses the ridiculous in his book Matilda to expose subtle, abusive parenting, Joon-Ho’s far-fetched thriller expands our window of tolerance for engaging the uncomfortable reality of the disparity between affluence and poverty.

At one point in the film, the Kim family has their almost subterranean apartment flooded by a overnight torrential downpour. Images of floating possessions, a backed up sewage system and a night in a makeshift shelter at a school are a gut-punching contrast to the Park family’s naive relief over the rain’s benefit to their lawn the next morning. Parasite helped me concretely understand the privilege of welcoming rather than fearing the weather.

And that has stayed with me as I’ve shoveled snow almost daily this past week to keep my inclined driveway safe for my teenage driver. Privilege is the luxury to roll my eyes at the forecast or enjoy watching the snowfall from beneath a quilt, rather than fearing its effect. The means to insure my teenage driver, owning a family car (much less two!), and being able to afford a shovel are all privileges of wealth.

Snow has concretely anchored me this week to the flood scene in Parasite, but other threads in my life are also woven into the reality of my privilege.

Last week I began a new role as a case manager for the nonprofit Bridge of Hope. Tonight I’ll visit my first client, a single mom enrolled in our housing subsidy program designed to prevent her recidivism back into homelessness. I am anticipating this new role will force me to straddle both my present privilege of being a two income family as well as my past childhood of living not far above the poverty line as the child of a single mother.

Last week I also spent hours on the phone seeking to secure a medication that has helped me successfully manage a chronic illness. My copay for the first two years of my diagnosis was $0 but insurance companies and their specialty pharmacies altering the “tiers” of the drug I rely on have now made it unaffordable. I’m straddling both the privilege of having health insurance and not qualifying for medicaid as well as the handicap those are, ironically, in seeking financial assistance.

Parasite. Privilege. Snow. Homelessness. Medication. Any movie that helps me more deeply engage my own personal experience of privilege, as well as feel seen in ways it is absent in my life, is indeed Oscar worthy!

What did privilege look like for you growing up? In what ways did you experience affluence and poverty—either physically or metaphorically? What story of straddling privilege and the absence of it do you need to tell in order to be more compassionate to yourself and others in the present?